“You can do this work and make a lot of money and have a good life. I am forty years old. I do this job for eighteen years.”

It is my Junior year at Antioch and I am in Amsterdam, conducting interviews with prostitutes as part of a Comparative Feminist Studies program in Europe. On my program application I have described my experiences in Mexico and back home in Ohio as “participant observational research.” I am claiming to study "women's participation in the sex industry." I am a student, a researcher, a feminist—not a sex worker. I am not here to talk about myself. I am not "out," not yet writing memoir. In an effort to make sense of my self and my experience, I am interviewing other women, asking them the questions I could not yet ask myself.

Valencia is an Indonesian woman with dark skin and pale gray eyes. She sits at a kitchen table next to a dripping sink and a small buzzing fridge in the common room of the brothel where she works. Other girls in various states of dress come in and out, going to the fridge and pulling out a yogurt or a soda, or nuking their coffee in the filthy microwave on the counter. The space reminds me of the back room of a grocery store where I worked as a teen, only here was slightly cleaner. Someone has handwritten a sign in three different languages that hangs above the sink. In English, it reads: Please Do Your Own Dishes. Valencia sits across from me, crosslegged in her underwear, smoking a cigarette that she ashes into a Styrofoam cup. She inhales each question, pausing momentarily before exhaling to answer, smoke chimneying from her nose. Her nails are nicotine yellowed. Her lips purse around each word. She is flippant, coy. She is so disengaged from the interview process—there is a dilated look to those watery gray eyes—I think maybe she’s on drugs. I don’t know for sure, and I don’t ask. Instead, I ask about her decision to become a prostitute.

“I didn’t want to go to school,” Valencia shrugs. “If you go to school, you have to study hard, and then find a job. Only if you work hard can you make money. I prefer to take the easy way. It’s not bad and it’s exciting,” she adds. “I have a normal life.” For Valencia, sex work is work. She clocks in, puts out and goes home to care for her three young children.

“Growing up,” I ask, “Had you always wanted to be a prostitute?”

“Of course not,” she snaps, pausing to look at me as if I am stupid. “Of course you never think, oh, someday I am going to be a prostitute. But,” she shrugs again, “you learn. You see what goes on. You try it. It’s normal enough, and you like it. I like the stupid men,” she says and laughs. “They pay for a half an hour and they come in five minutes. I say to them, ‘why did you shoot your money away?’” She laughs again. Tut tut tut. Smoke puffs out her nose.

“Do you think it’s better, working in Amsterdam versus working in other countries?” “Oh yes, here is better.” “In what way?” “Well, here they control everything. Everything you see is controlled. Our names are registered. We give our names to the police so that if somebody’s killed they’ll know who it is. It’s a very safe feeling here in Amsterdam. I’m really careful and I select my customers. I always talk to them before I let them in my room. I get a good look. If somebody’s looking for trouble I don’t take them in.” I ask, "How can you tell if someone’s looking for trouble?” “I use my intuition,” she says. I wait, but Valencia doesn't continue. That’s it? I think. How do you know you can rely on that? I ask, “Have you ever gotten a bad feeling from someone and turned them down?” “No,” she says. “I’ve never turned a customer down.” Again, I wait, but Valencia looks bored. She asks, “Are we almost finished?”

Valencia wants to talk about America. She acts as if she doesn’t understand my interest in her profession. I keep asking her questions and she keeps trying to redirect the conversation to me. She tells me, “You know, in Holland, it is not allowed to carry guns.” She tells me she thinks American food is disgusting. “Do you eat McDonald’s hamburgers?” she asks. “What is it called? A Big Mac?” She makes a face. I feel, at times, that she is making fun of me, trying to get the better of me. I am frustrated by a feeling of not being in control. The interview does not go well. She simply has no feelings about her occupation—none, at least, that she is willing to share. In the end, Valencia gives me her address, offers me cash and asks if I could send her a Talking Elmo doll for her youngest child. I refuse to accept the money; I do not keep her information.

It’s normal for me, she kept saying. “You see, it depends. I don’t know if you go to the discotheque, but many girls do. You see a nice boy, you try to do something maybe to catch his eye. Then, maybe after two or three dates or something like that”—she made a gesture with her wrist. “So here it’s the same, except we get money for it. It doesn’t stay with you a long time when you go to the discotheque, and it doesn’t stay with you a long time here. But actually it’s fun, though, so it’s not so…” she laughed, dryly. “If you meet a nice boy—you get money, and you get fucked.”

* * *

Growing up, what were my wishes? Who or what did I want to be? Growing up, had you always wanted to be a prostitute? No. Growing up, I had wanted to be a pony. I had wanted to be a ballerina. I danced in my socks in the kitchen with the lights out while my parents, in the other room, watched TV. I wanted to be a lawyer. I didn’t know what lawyers did, only that they were important. I told my teachers my father went to Harvard. Neither of my parents had gone to college. My father was a salesman. I don’t know what he sold. Before that, my father had raced horses. He was a driver and trainer. I grew up at the racetrack, a little girl with her daddy, mesmerized by the ponies with their sexy names—Triple Lex, Strike It Bitch, Camelot Trot, Dream Come True. My father loved his horses.

Growing up, my mom, dad, brother and I lived in the basement of what had been my grandma’s house. When my grandmother died my freshman year of high school, my parents inherited the house and we all moved upstairs— all except my father, who stayed downstairs in what had been him and my mom’s room in the basement. In retrospect I realize this was the moment when my father turned off, turned into himself and shrunk further and further away from the rest of us until, one day, he was gone. One day, my Senoir year of high school, I came home from school and my mother told me my father had left. He'd moved out, just like that. To this day, I haven't seen him since. To think of my father is to think in abstract. Like a lesson in perspective, a road defined as two lines narrowing to a single elevated point: my father.

I wanted to be beautiful. I wanted to be taken care of. I wanted to be rescued. I was sexualized long before I sexualized myself. Even as a child, I knew the way men looked at me. I knew what it meant. In Mexico, men called out in the street and hissed when I walked past. Even older men—friend’s fathers, male teachers—even as a little girl. Even in grade school, I knew what it meant to be a woman and I was no longer a little girl. At nineteen years old, I was well aware that my body had become a woman’s body. Even as a child, I knew what that was worth.

Growing up in a home without food, you are always hungry and every kind of hunger, it seems, feels like you are starving. Of such an appetite, you become ashamed. When your needs become confused with desires, you always want more. In a world of unreliable people, you learn to rely on yourself. Stripping was one way I learned to get noticed, and being noticed—I thought—is what it took to survive.

On the TV show The X Factor, Simon Cowell challenges his contestant: "You have three minutes to change your life." Like a contestant on a game show, I thought I'd get in and get out. Big money, no whammies. What happens in Mexico stays in Mexico. I can make the money I need to make to make my dreams come true, and no one back home will ever have to know.

Growing up, I wanted to be an American Idol. Debbie Gibson. Tiffany. I wanted to live the American Dream. Growing up in a country where winning a contest is made out as someone’s only opportunity to make one's dreams come true, today I recognize my becoming a sex worker less as a distaste for hard work as it is indicative of the lack of equal access to meaningful work. Pair that with the way meaningful work is denigrated and celebrity is rewarded—compare Snooki's draw to Toni Morrison's—and we've got a culture ripe for the lap dancer.

One problem with sex work is that it’s not forever. If I could offer some advice to girls just starting out in the business, I would say to learn how to handle your money, and go to school. Growing up, no one ever taught me how to handle money. In my home, growing up, there was no money to be handled. Sex work taught me to make money, as much and as fast as I could. But I never learned what to do with it, and it never brought me the happiness or security I assumed that it would. I always told myself when I graduated from college I'd quit sex work for good. Then, I'd have a degree. I’d find another, even better job—a job that paid just as much, doing something I enjoyed even more. Stay right-sized about your choices, I would tell a girl just starting out—as hard as that is. Listen to how it feels. Listen to your heart, not your head.

James Baldwin writes that "of traditional attitudes, there are only two—For, or Against." He goes on: "I, personally, find it difficult to say which attitude caused me the most pain." Baldwin was speaking in 1955 as a "negro" of the "negro experience," but as a former sex worker, I can relate. Since first stripping off my clothes for money I have struggled to make sense of myself and my experience within the confines of society’s limited sexual imagination. From early on, speaking for myself meant straining to somehow fit my experiences and my opinions of my own experience—at times, it felt, of my very self— into one of two dichotomous positions: for or against. Early on in my activist career, I became “pro-sex industry,” even when being so meant denying aspects of myself, my relationship to myself and aspects of my experience that were undeniably consequential, even more so precisely because they were refused accurate assessment.

To quote sex worker-artist "Mad Kate" Kathryn Fischer, from a private correspondence: “It’s a strange edge some of us are forced to live: Feeling obliged to, but not wanting to, take sides. I mean that because the threat of falling back into our old lives—one where none of this is okay, one where all of this is hidden and wrong and disregarded, is so real, that we’d rather pretend it’s all perfect and beautiful rather than risk losing it altogether.”

If I could offer my sisters one word of advice, I'd say: be real. Be as real as you can be. Tell your truth as honestly and as often as you can tell it. Listen to other people, particularly when you disagree. Listen to yourself when you're telling your truth. Root out your own inaccuracies. Aim for a harder, more complicated truth. I didn’t do this. I couldn't. I listened only to logic, which told me there was nothing wrong with what I was doing. Because there wasn't—logically at least. Logically, I still believe this to be true. Morally, I know there is nothing wrong with sex work. Sex work is not inherently wrong. Sex work is not inherently dangerous. Sex work was, oftentimes and in many ways, something I enjoyed. That said, sex work was a far from a perfect occupation. Prostitution, in particular, was not the job for me. Sex workers do not deserve to be hurt or suffer because they sell sex. But they do. I was. I did. This is not a perfect world, and not everybody has the constitution for this kind of work. I didn't, and the reasons why I was doing it were in many ways fucked up. For me, sex work was not just work, a job like any other. It is equally disingenuous to say I did it only for the money. Yes, stripping began as a means to socioeconomic opportunity, but the prostitution was about something else. What began as a solution to my problems, turned into a problem of its own.

For me, the risks of prostitution proved a lot more subtle than the threat posed by traffickers, pimps, serial killers or the one in a billion chance of getting AIDS. I was 27 years old. Fresh from a nasty break up, still licking my wounds. I sold what amounted to the “Girlfriend Experience,” GFE for short. I met my clients at a bar where we had a drink or two, before going back to my place or his. It was set up like a blind date, in all ways normal except this blind date would end in sex (and he would pay me). In my ads, I described myself as a student, studying literature (a half truth). I was bored and curious, looking for a little fun. I was a writer, pursuing an MFA. For a period of the time, I had a daytime gig, working as a consultant for a high-profile nonprofit advocating against sexual assault. I wanted it both ways and, logically, I should have been able to have it that way. I was a feminist. I was many things but I was not, in my mind, what people thought when they thought prostitute. I was not not the drug addicted streetwalker being arrested on Cops. I was not the high class call girl who’d scandalized the VIP. I was normal. I thought, just like you. Just like you, I thought, so long as you didn't sell sex.

Looking back today, I can see that my isolation—for all the dangers it exacerbated—was a form of protection as well. I believed that I was different from the kind of girls who did this sort of work. For one, I was educated. I was white. I was American born. I was not like them. I wouldn't be doing it forever. I was a "non pro." It was not my career. I was no victim, no not me. I'd never been raped or sexually assaulted. I wasn't molested as a child. I would not become the body abandoned on the beach. Like women I had interviewed years earlier, I relied on my own intuition to keep myself safe. Relying solely on ones' self and ones' trust and faith in the client is—I realize today—naïve, at best. Today, I realize I am in no way exceptional. I'm just like a hundred other hookers, and I was lucky. I was never a victim of a violent crime despite the fact that I did nothing to protect myself. But even though I was never a victim, I can't say I escaped from the industry unscathed.

As much as I wanted to believe that my job wasn't affecting me, from the beginning, sex work compromised my relationship to my family and community. Lying to my family and other people I loved, I suffered constantly from a feeling like something I was doing was wrong—although what, exactly, was never clear. I kept working in the sex industry long after I stopped enjoying the work and well after it was financially necessary, as if by quitting I would be admitting that I was wrong for ever having done it in the first place. I also felt— and, in certain ways, had made myself—reliant on the income. After my brief period of selling sex, I found myself virtually unemployable. Having grown so accustomed to the lifestyle of making hundreds of dollars an hour for working when I felt like it, doing what felt like very little work and doing whatever I wanted with the rest of my time—not to mention the inexplicable gap in my employment history—I didn’t want to have to then look for a “real” job.

Outside of paid encounters, it must also be said, my sexual behavior was incredibly risky, for the reasons academics suggest: by engaging in unprotected anal sex, for example, with a boyfriend or potential boyfriend—something I would not do with a client—I defined the one interaction as "personal" and the other as "professional." My standard for what constituted a “boyfriend” at that time, it also must be said, was reduced to anyone that was non-paying (no matter for how briefly or how little I knew the man).

Not everyone's experience is like mine. I don't claim to represent all sex workers. My only claim is the right to represent myself. Some people love every aspect of the work whereas other people hate it completely. Some people's experiences, like mine, are neither entirely good nor bad. I have met a lot of sex workers who suffer from the stigma and feel a sense of shame, despite all logic and experience. They live their life in secrecy, fearing something bad will happen—waiting for the other shoe to drop. Fearing they will somehow be "punished" for what they are doing, fearing without reason that what they are doing is "wrong." It took me a long time to realize that I felt this way, and an even longer time to realize that just feeling this way was a negative consequence far worse than so many others I imagined—a "punishment" in and of itself, and one that, today, I realize I didn’t deserve.

The more we are allowed to speak, the more reliable become our narratives. To quote Mariko: “The more I speak, the faster I heal.” “We need to tell our stories,"writes author Elissa Schappell. "It’s a form of currency, catharsis, it’s how we frame our experiences. It allows us to create and take control of our identity.” Elissa is speaking as a woman on the importance of reframing experiences from a non-male point of view. I would say this is particularly true for sex workers, even though the consequences of speaking, for a sex worker, can create its own suffering, as the details of Mariko’s story—and mine—clearly attest.

I see my truth today, which is all I ever wished for. And the truth is a lot simpler than I had feared. For as long as I could remember, I had always suffered from and remedied—to greater or lesser success—feelings of not fitting in, of not belonging, of being different. The extent to which I felt this way, compared to how other people experience these feelings, I didn't know. At first, working in the sex industry helped me to feel less lonely, but then in time, it only made these feelings worse. Without people with whom I felt I could be honest, and people with some knowledge and insights of their own, I felt compelled to suppress whole parts of my experience, particularly the bad stuff. What would have helped me most at the time that I was having sex for money was to have heard stories from women like myself, women actively engaged in the business—as well as from women who’d moved on from sex work, particularly those women who’d made it through with or had somehow recovered a healthy sense of self. Without such community, it took me much longer than necessary to exit the industry and, only since having done so have I begun to develop a more honest, right-sized understanding of what I’d experienced—thanks entirely to the help of the many friends and associates I have today, current and former sex workers of all stripes, brave enough to have shared with me their stories.

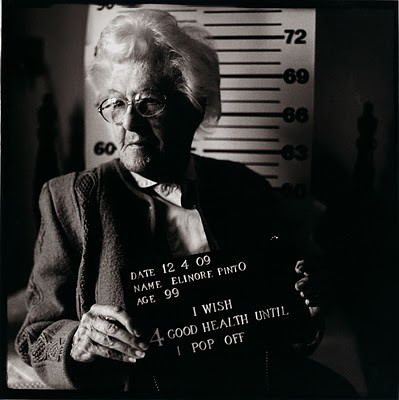

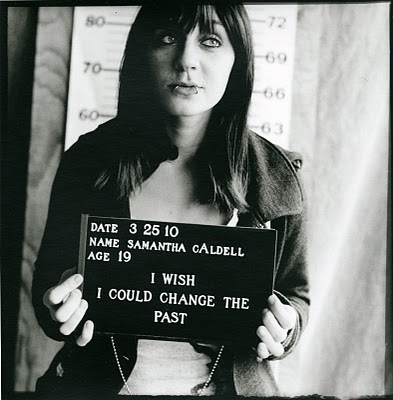

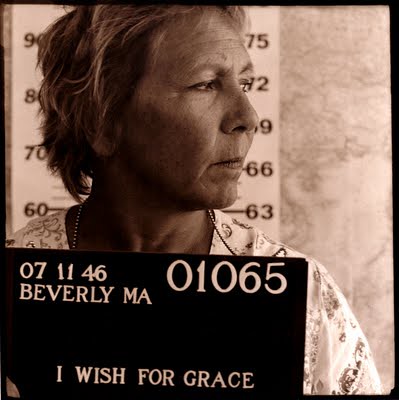

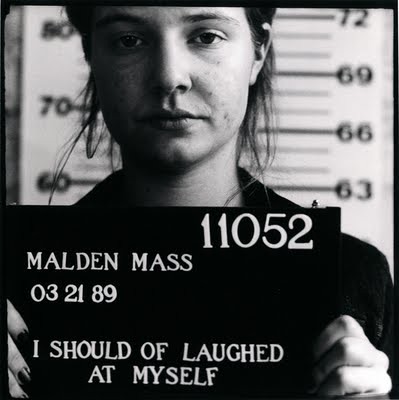

Special thanks to all the current and former sex workers who shared their stories as part of this series, and to Lauren Gillette for giving me permission to illustrate this story with her photography, taken as part of project called Wish/Regret. None of these women, incidentally, are sex workers (as far as I know). Here is Lauren, about Wish/Regret: "I am attempting to bear witness. When Marvin Gaye called out, 'Can I get a witness?' I heard the call. And have felt to pull of projects that allows me to collect, chronicle and archive, tell and retell. I am working to reveal something emotive and intimate about each subject. To spark that last piece of the puzzle, a visceral thread of recognition in the viewer. A big heartfelt thank you to the 50-plus Wish/Regret participants that showed up and parked themselves in front of the Hassleblad and height chart, stared into the camera and shared something truthful about themselves." More at Lauren's blog.